In my last post, I attempted to articulate a framework for thinking about God in and through our encounters with one another. I stated, provocatively perhaps, that it is only and always within creation—through our embodied experiences—that we encounter God. Therefore, we must think seriously about what it means to encounter God in and through each other’s embodiment, each other’s incarnation.

However, we do not simply encounter one another. There are narratives that shape the ways in which we encounter one another and how we make sense of such experiences. I want to focus this blog post on narratives and how they shape our encounters.

part II: narratives of the Other

“Stories make and unmake worlds.”

— Laurel Schneider, Beyond Monotheism

Words are powerful, and their utterance, like any act of power, is never merely neutral. No, the narratives they weave are making and unmaking our world. Once ingested, words get busy constructing images and concepts, building the narratives through which we attempt to make sense of everything—from wars to immigration to police brutality to meeting someone new to one’s own place in the cosmos. Narratives have the power to open us (bringing connection and healing), close us off (thereby re-inscribing fear, divisions, and hostility), or promote apathy.

This becomes particularly salient when encountering someone or something “strange,” “foreign,” or new. As such a moment of encounter makes potent, so much in our world and daily lives evades our comprehension. “Other” people act, love, speak, and look differently than “us,” and so we form a narrative (consciously or not) to help us make sense of why “they” do it.

As the renowned social and cognitive scientist Dan Sperber fascinatedly points out, somehow, without explicit instruction all humans learn to treat symbolically information that defies direct comprehension—that is, things we have never seen, felt, touched, tasted, or heard before.[1] Thus, in the face of the “Other’s” Great and Awesome Mystery homo sapiens become homo poeta, “humankind the meaning makers.”

We interpret each Other.

Indeed, as infinite Mysteries we treat each other symbolically (including those closest to us whom we *think* we know so well), conjuring up concepts and images that we have acquired over time through the narratives we’ve consumed—willingly or not. Consciously or not, it is through these narratives that we construct our physical world and “make sense” of (interpret) the Other who defies our comprehension, and whose “foreignness” might even incite fear within us.

Yes, in such a context, words are powerful. They are not neutral. They make and unmake worlds, for in every moment the stories they weave shape the decisions we make about how to relate to one another—both interpersonally and through the social structures we are creating.

We must therefore become conscious of those narratives by which we are conceiving and living in the world. Even more, we must “develop new habits of the mind” so that we might construct an alternative narrative that gives space to and celebrates differences / diversity.[2]

As theologians and others have been increasingly pointing out over the past half-century, narratives about our relations to one another—such as “us” vs. “them”—are intricately tied to our narratives about God. So it is to such narratives we now turn.

§ orthodoxy and the narrative of God’s otherness

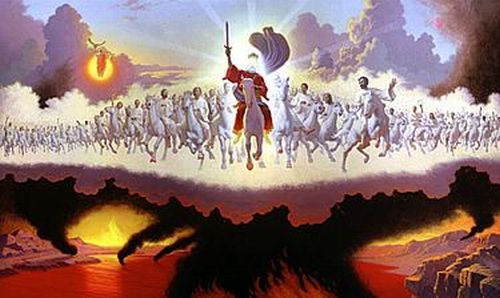

Since Rudolf Otto and Karl Barth, two of the most influential 20th century theologians, the notion of God as “Wholly Other” has permeated the modern western mind, from the theological academy to the church to even non-Christians and avowed atheists. This Wholly Other One is not only distinct from humanity and irreducible to its conceptions, but “He” [sic] is also absolutely separate from them.[3] Indeed, God is “imagined as inhabiting, indeed constituting, an external space of ontological elevation which is also the eternal telos (“end”) of all creatures,” even if we can say God is multiply present in creation.[4] Or, to put it more plainly: God is in heaven and you are on earth (and nothing can bridge that grand canyon but Christ).[5] Such imagery, however, stems from and insists on hierarchical and platonic thinking, where the immaterial divine realm alone is preeminently real and immutable and this lower, earthly one is but a fading placeholder.

Echoing Elizabeth Johnson’s incisive refrain, “The symbol of God functions,”[6] however, we proceed recognizing that conceiving God’s otherness as entailing separation from creation has negative implications not only for our visions of God, but also for the created world because it sets up real difference as antithetical to close relationship. Indeed, theological notions of God’s transcendence/otherness are inseparable “from theological notions of what a human being is and, as a consequence, of the meaning of inter-human differences.”[7] Therefore, “ideas about the divine Other are always related to our perceptions of and relationships with the human Other.”[8]

As such, symbolic representations of God’s otherness have tended to shape and perpetuate narratives that divide our world between “us” and “the Others.” And not only is there division, but the division itself continues the hierarchy along a descending chain of dependency away from God to men and then women, with further subgroupings of gender, race, class, ability, etc. along the way. With a painful awareness of the ways in which this “orthodox” hierarchical notion of God as Wholly Other and thus absolutely separate from creation has functioned throughout history to rationalize and justify the colonization and subsequent oppression of peoples both throughout history and in the present, we ask ourselves: is this really the only faithful way to envision God?[9]

Perhaps the most dominant contemporary western response to the violent and dehumanizing history of this “orthodox” notion of inter-human difference is a narrative that privileges notions of sameness.[10] Theologian Laurel Schneider has dubbed this narrative, “the Logic of the One.” Recognizing the difficulties posed by our differences, this reactionary narrative has simply sought to flatten them. Through a totalizing narrative that emphasizes homogeneity by wrapping each distinct Other into a universal One, this narrative promotes assimilation into the dominant group through the undressing of an Other’s otherness and the putting on of “like-us-ness.”

Intentionally or not, however, by downplaying our irreducible differences this narrative becomes a tool for maintaining the (typically unjust) status quo. Indeed, from the colonial project in its attempt to make one tribe out of the many nations,[11] to the Third Reich and Hitler’s desire for a single pure race, to the “All Lives Matter” reaction to the “Black Lives Matter” movement, the narrative has been used throughout history to justify the domination, subjugation, and silencing of peoples.[12]

So we ask ourselves again: is there another faithful way to imagine God?

§ relational transcendence—re-imagining divine otherness

In light of the tragic failures of the narratives of otherness above, we return to theologian Mayra Rivera’s profound theological paradigm shift from a hierarchical transcendence of the Wholly Other One to a model of relational transcendence, which emphasizes that “it is always and only within creation that the divine Other is encountered.”[13] Indeed, relational transcendence refuses “the ‘hard boundary’ between the divine and the created;” rather, it affirms that “the beginning, sustenance, and transformation of the cosmos are intrinsically divine.”[14] Indeed,

“Creation is the extension of God.

Creation is God encountered in time and space.

Creation is the infinite in the garb of the finite.

To attend to creation is to attend to God.”[15]

Furthermore, in such a theology incarnation—flesh, bodies, faces, eyes—is paramount. And because bodies are particular—each one being unique/irreplaceable—incarnational theology also refuses to be reduced to the homogenizing narrative of Oneness described above. Indeed, the particularity of God’s fleshiness lies at the heart of the Christian Jesus,[16] but contrary to the narrative of the One which limits incarnation to Jesus alone, relational transcendence affirms that the theological revelation of the incarnation of Jesus of Nazareth points beyond itself: the flesh of the entire cosmos “emerge[s] from and participate[s] in the divine.”[17]

At this point, we must emphasize what Laurel Schneider has called the “metaphoric exemption,” reminding ourselves that “we, theologians and dreamers of God, are not God just because we are a noisy dream of God.”[18] And yet, we are “finite fragments of divine matter,” the radiant glory of God, as (St.) Iranaeus so boldly articulated 19 centuries ago. It is not simply that “God is in all things, as essence, presence, and potential,” but that the Trinitarian life is “intrinsic to all things.”[19] God is that which “envelopes the immense organism of which we are all part.”[20]

Once again, this is not to erase or downplay the Other’s difference—God’s or our own. On the contrary, I am implying and emphasizing it. In a model of relational transcendence, however, neither God’s otherness nor our own need be equated with separation. Instead, our irreducible differences allow for the intimacy of relationship (and the proximity it implies), “where the common is what surprises” and proves mutually—and radically—transformative.

Indeed, “like a soft breeze that blows over words written in the sand,” we can hear Augustine whispering softly in our ear, reminding us: “If you have understood, then it is not God. If you were able to understand, then you understood something else instead of God. If you were able to understand partially, then you have deceived yourself with your own thoughts.”[21] Indeed, to understand God would be to claim to grasp God’s irreducible otherness—to grasp God!

Through a model of relational transcendence we can also say that if you have “understood” any human Other, then it is not that Other but literally a figment of your imagination!

Our interpretation of the Other must never be mistaken for the Other him/her/themself.

Importantly, there need not be a contradiction here “if we can imagine God to be big enough to break the laws of theologians, to incarnate freely, to respond, again and again, in the flesh of the world.”[22] As Mother Teresa (and Jesus himself) was fond of saying, Jesus comes to us every day in disguise.

Oh, the scandal! Would that we had hearts to see! God and we are irreducibly Other—not absolutely Other—and this makes all the difference. Gathered together in God’s own infinite singularity, space is carved for the risky and vulnerable intimacy of encounter, of relationship, with each Other. In God’s nurturing, non-controlling embrace, each of our own irreducible infinitude—that which makes each of us Other, distinct—touches, like the quivering lips of forbidden lovers.

_______________________________________________

in my next and last post, I will attempt to offer a poetic articulation that seeks to evoke the power that this narrative opens for experiencing encounter.

(and now that you’ve suffered through this long post, if you’re interested in the ideas I attempted to articulate above, I strongly encourage you to listen to this brilliant TED Talk by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie about the danger of a single story)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Dan Sperber, Rethinking Symbolism. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1975, 148.

[2] Rivera, Touch of Transcendence, 118.

[3] Ibid., 4.

[4] Ibid., 23; emphasis mine.

[5] Ibid., quoting Karl Barth, Epistle to the Romans.

[6] Elizabeth A. Johnson, She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse. New York: Crossroad, 1992.

[7] Rivera, Touch of Transcendence, 2.

[8] Ibid., 128.

[9] Cf. Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, The Power of the Word: Scripture and the Rhetoric of Empire. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. 2007, 97.

[10] Rivera, The Touch of Transcendence, ix.

[11] See especially the chapter entitled “Colenso’s Heart” in Willie James Jennings groundbreaking book, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race.

[12] I can’t really do these narratives nor a discussion of their difficulties justice in such a short post, but if you’re interested in further reading on the topic, I highly recommend Willie Jennings’ book above, The Christian Imagination, again especially the chapter “Colenso’s Heart,” or Laurel Schneider’s book, Beyond Monotheism: A Theology of Multiplicity, especially Part I: “The Logic of the One.”

[13] Rivera, The Touch of Transcendence, 2. Emphasis mine.

[14] Ibid., 133.

[15] Pirke Avot, 6.2.

[16] Ibid., 159.

[17] Rivera, 128; emphasis mine.

[18] Schneider, Beyond Monotheism, 154.

[19] Rivera, The Touch of Transcendence, 46; quoting Ignacio Ellacuría.

[20] Ibid., 136.

[21] Augustine, Sermon 52, c. 1, n. 16.

[22] Schneider, Beyond Monotheism, 154.