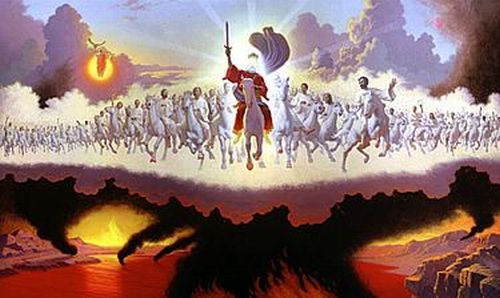

Everyone seems to have their own ideas and images as to who God is: whether it’s an old white man in the sky with a flowing white beard,

a God who is Love

or a tribal God who leads His people in battle against His enemies, as in the God of the crusades or even the God of Christianity vs. Islam vs. Judaism vs. Atheism etc.

Martin Buber, who was one of the great religious philosophers of the 20th century once said that the word “God” has been so defiled and covered with blood that it should be retired from our vocabulary, at least until it recovers from such abuse. (1)

But as much as we are frustrated by the pervasive and disgusting misuse of this word, humanity seems unable to sever itself completely from the quest to encounter the reality behind the word. I think that’s why there are so many who identify as “spiritual” even if not “officially religious” in our generation.

I think Jane Fonda captures this well. In an interview with Rolling Stone magazine, she was asked about her controversial late-in-life conversion to Christianity (because, why the hell would a well-educated and well-off adult convert to Christianity?!). In her response, she spoke of being drawn to faith because

“I could feel a reverence humming in me.” (2)

I like that.

Try as many of us may, we simply cannot escape this reverence that hums within us when we experience moments that are deeply life-giving, moments where we sense something beyond that which meets the eye.

We recently entered the Advent season, a season filled with longing and preparation where we reflect on the state of our souls and the state of our world as we await the coming of God in that “8lb 6oz newborn infant Jesus, don’t even know word yet, just a little infant, so cuddly but still omnipotent” on Christmas. I love the Advent season; I love the lectionary readings that draw us into the ancient narrative of longing for God to redeem creation. With them, I look deep within to my own stirring soul and out at our world groaning with the pangs of brokenness, and I, too, yearn for God to bring shalom, wholeness.

I do have a complaint, though. I am frustrated that conversations about Jesus’ birth narratives, including the virginal birth, get limited to whether or not history literally happened the way Matthew and Luke present it (note: the birth stories are only part of these two Gospels. Mark and John–and Paul in his letters–apparently weren’t concerned enough with the birth of Jesus to write about it).

I believe the God we encounter in the incarnation—in the belief that God took on human flesh in Jesus—is infinitely more profound if we go beyond a sole focus on historical fact and instead probe the profound depths of insight it gives us for thinking about God. In a world where God is too often used to exclude and perpetuate injustice, I believe the incarnation gives us a picture of a God who is:

with us,

for us,

and ahead of us. (3)

“O come o come Emmanuel” is my favorite hymn of this season. Emmanuel—which literally translates to “God with us” is the longing cry and the expectant song of hope of this season. It is our reminder and our declaration that the God we believe in does not sit idly by while we experience the depths of despair or heights of joy or the mundane in between. One of the most profound truths of the incarnation and the Christmas stories is that God is not distant. And not only is God not distant, but God has actually entered into the messiness of creation with all its chaos, injustice and suffering.

This idea is taken to profound depths when considering Jesus’ life and death. Just as God, in Jesus, was with the people of Jesus’ day, especially in solidarity with those on the margins, so is God with us—all of us—but especially those on the margins of our society and those whose humanity has been denigrated. And get this—this is crazy!—through the lens of the incarnation, not only is God not distant but, paradoxically, in Jesus’ death on the cross, God was crucified! Wrap your mind around that!

Through the incarnation, we encounter a God who we can not only say identifies with our suffering, but even suffers with us. A God who suffers with us!

Not only does the incarnation reveal a God who is with us, it also reveals a God who is utterly and irrevocably for us. And perhaps here I should clarify: by us, I do not merely mean Christians. No, God is utterly and irrevocably for all of creation, as all of creation is made in the image of God. If you’ve been told that you are “less than” or an “abomination,” or a “deviation from the norm;” if you’ve been denigrated, excluded or marginalized—not only is God with you as you endure this dehumanization, but God is for you as you journey to truly claim, celebrate, and live into your identities and truest self.

In pondering the “who” or “what” or “when” or “where” or “why” in the for-ness of God, I return again to Jesus as the particular through which to make sense of the abstract and ultimately mysterious Universal Reality we call God. When we do that, we find a God whose gospel critiques pride and arrogance, which divide people, and elevates humility, empathy and compassion, which bind us together and enable us to find our own humanity in and through one another. Jesus embodied this message by not only standing in solidarity with the marginalized and denigrated of his day, but by daily advocating for their full inclusion—for the full recognition of their humanity by the people and society denigrating them (namely the religious leaders of the day).

The God revealed in the incarnation of Jesus is a God who is utterly and irrevocably for you as you journey to truly claim, celebrate, and live into your truest identities and truest self.

Lastly, God is ahead of us. For me, this belief is grounded in the inherent reality that God is ultimately beyond full human comprehension. In fact, the moment we begin to insist that God is confined to any one particular image or set of images, we risk idolatry—worshiping an idea about God rather than the Ultimate and Ineffable Mystery that is always beyond, always more than our words can say. St. Augustine put this quite well in one of his sermons when he said, “If you have understood it, then it is not God.” (4)

To make my point, let me give you some of the ways in which God is conceived or imagined throughout the Bible:

In addition to the preeminent image of Father, God is depicted as mother, a female beloved, companion, and friend. In addition to King, God is an advocate and liberator, a shepherd, midwife, farmer, laundress, construction worker, potter, artist, merchant, physician, baker woman, vinedresser, teacher, metal worker, and homemaker. Did you know that imagery is used of God as a woman giving birth, nursing her young, as a hovering mother bird, an angry mother bear, and a protective mother hen? In addition to God as a Being, God is depicted as a cloud, a rock, wind, fire, a light, refreshing water, and life itself. (5)

Clearly, we aren’t meant to take any of these literally. God is always beyond the literalization of words and images. What this myriad of images—and their contexts in the Bible—shows us is that God is revealed to us in new ways as we encounter new situations. It’s not that God changes; rather our ability to perceive the “when” “where” “why” and “how” of God changes.

In the Hebrew Scriptures—the Old Testament—there’s a story of a man named Jacob who has a magnificent dream one night. When he wakes up, he exclaims, “Surely God was in this place and I, I wasn’t aware of it.” (6)

The work of each generation and each group of people is to “wake up” and have eyes to see and hearts to discern the “wheres” and “hows” of God’s presence in light of their present context and realities, even as they remain grounded in their historical tradition. For example:

“Who,” “what,” “when,” “where,” “why” and “how” is God in light of the history and experiences—of denigration as well as life-giving—of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals? or African-Americans, or black people worldwide? or women? or people with disabilities? or the homeless and poor? or any combination of these and/or other identities? or in light of the ecological crisis our generation faces? the list could go on. . .

In his most recent book, What We Talk About When We Talk About God, Rob Bell writes that in the Bible we encounter a God who meets “people, tribes, and cultures right where they are [but then] draw[s] and invit[es] and call[s] them forward, into greater and greater shalom and respect and rights and peace and dignity and equality. It’s as if human history were progressing along a trajectory, an arc, a continuum; and sacred history is the capturing and recording of those moments when people became aware that they were being called and drawn and pulled forward by the divine force and power and energy that gives life to everything.” (7)

The idea of God incarnating a poor Jewish peasant was inconceivable for many in its 1st century Palestinian Jewish context. It required a radical freedom of imagination and a deep encounter with the divine.

So here’s my question to you: this Advent season as you prepare your heart to discover and encounter the incarnation anew—the truth that God is with us, for us, and ahead of us—how might the divine be drawing you forward? And what insights might your own encounters with the divine provide our community for “who” “where” “when” “how” and “why” is God in our midst?

all my love, eric joseph

—————————————————————————————————————-

(1) from Elizabeth A. Johnson’s Quest for the Living God, p. 9

(2) unable to access article without a subscription; however, she states her point similarly on her website here: http://janefonda.com/about-my-faith/

(3) I’ve borrowed this framework from Rob Bell and his 2013 book, What We Talk About When We Talk About God. The way I develop it using the lens of the incarnation, however, is my own work.

(4) Sermon 117.5

(5) Johnson, Quest for the Living God, p. 21

(6) Genesis 28:16

(7) pp. 164-165